Conservative Christians like to deny it, but the Bible is riddled with contradictions, by one count 439 of them.[1]

In this blog, I will look at why they are there and how much they matter.

Yahweh and Elohim

If you read the Book of Genesis, you will note it alternates between two different names for God: the Lord/the Lord God (Yahweh in Hebrew) and God (Elohim in Hebrew). In the 18th century, scholars noticed that if you separate the strands with Yahweh and Elohim, each strand will often make sense on its own. They concluded from this that two different source documents had been woven together to create Genesis (and the other books of the Pentateuch: Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy).[2]

By analysing the language, style and preoccupations of these different source documents, scholars eventually identified four of them, and in the late 19th century Julius Wellhausen synthesised these findings into a “documentary hypothesis” that would come to dominate Old Testament scholarship in the second half of the 20th century. This hypothesis proposed four authors: the Yahwist, the Elohist, the Priestly Writer and the Deuteronomist.

Though Wellhausen’s ideas have been subject to revision and debate over recent decades, his point about multiple authors stands. All non-conservative scholars accept that many stories in the Bible are told as doublets: two or occasionally more versions of the same story that either appear separately or have been woven together to be read as one.[3]

Thus, for example, Genesis contains two different accounts of Creation, the first by the Priestly Writer and the second by the Yahwist. And these two versions have different orders of creation. In Genesis 1, man and woman created together, after all the animals. In Genesis 2, man is created first, then the animals, and then, when none of them proved to be a suitable helper for him, woman.[4]

You see this again and again in Genesis, Exodus and Numbers, with doublets of all the central stories: the Creation, Noah,[5] Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, the Exodus and the wanderings of the Israelites. And this is one of the sources of contradiction in the Bible, because the Yahwist, the Elohist and the Priestly Writer drew on different traditions and had different preoccupations and agendas.

Forget That, Read This

The Bible isn’t one book; it is an anthology of texts written by dozens of authors over a period of almost a thousand years. It contains myth, polemical history, prophecy, proverbs, songs, erotic poetry, satire, philosophy, parables, biography, letters and forgeries.

And guess what – these writers didn’t always agree with one another. And it is likely that they often intended their version of events to replace an earlier version, not to lie alongside it or, even worse, to be woven into it.

Thus, many scholars think the Priestly Writer wanted to replace the Yahwist and the Elohist’s works with his own, because they gave too much emphasis to God’s mercy and not enough to his justice and the role of priests in mediating between God and man.[6]

Similarly, the author of Chronicles probably intended his books to “correct” the Deuteronomistic History (Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings), which he considered too negative, particularly when it came to David and his dynasty.[7]

Gospel Truth?

Something similar happened with the New Testament. Three gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) are known as the synoptic gospels because they are very similar. Most scholars believe Mark was the first, and the authors of Matthew and Luke had Mark in front of them as they wrote.

They seem to have wanted to replace Mark,[8] partly in order to add extra content and partly because they didn’t like its all-too-limited version of Jesus. In Mark, for example, Jesus heals a girl who is near to death. In Matthew, however, his miraculous powers are inflated and he raises the same girl from the dead.[9]

But the fourth gospel, John, is very different.[10] The overwhelming majority of incidents in the synoptics don’t appear in John, and most of the incidents in John aren’t in the other three. In Matthew, Mark and Luke, Jesus’s ministry lasts for a year and mostly takes place in Gallilee. In John, it lasts for three or four years, mostly in Judea. John puts the chasing of the moneylenders from the Temple at the beginning of Jesus’s mission. The other three put it at the end.[11]

It is clear that the author of John draws on a completely different tradition. And this is another source of contradiction. Through a process akin to Chinese whispers, the oral sources the Bible’s authors use evolved over time, and different authors in different places will encounter very different versions of events.

Opposition

Other contradictions appear because one text is written in direct opposition to the ideas contained in others. The Deuteronomistic History and many prophets present a very intolerant outlook: the only God that anyone should ever worship is Yahweh, and to do otherwise will bring down the wrath of God on our heads.

The author of Jonah would have none of this. His parable of the hapless prophet Jonah was written as a biting satire against this kind of attitude. This book stresses God’s mercy and forgiveness.[12]

Similarly, the Book of Job is another acerbic satire, this time directed at those who believe suffering is God’s punishment for sin. Ecclesiastes, a book that seems to owe more to Epicurean philosophy than to anything found in the rest of the Bible, explicitly rejects the idea that we can see divine justice in action: “In this meaningless life of mine I have seen both of these: the righteous perishing in their righteousness, and the wicked living long in their wickedness.”[13]

Problems with the Text

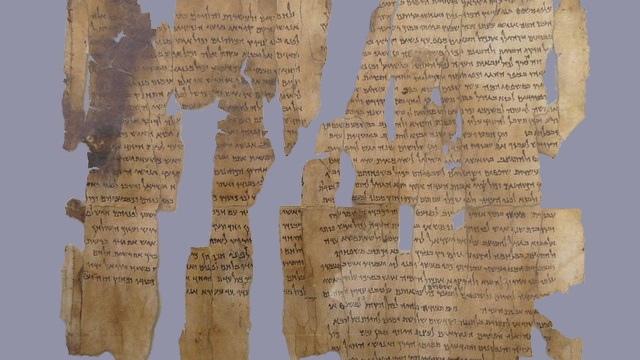

A final thing to note is that we don’t have an authoritative text of the Bible.[14] For the Old Testament, we have three families of texts: the Masoretic, the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls, and there are significant differences between them.

The Masoretic texts are in Hebrew and were transcribed between the 7th and 11th centuries CE. The oldest complete text is known as the Leningrad Codex and was completed in Cairo in the year 1008.

The Septuagint is a Greek translation of an older Hebrew version of the Old Testament. It was composed, again in Egypt, between the 3rd century BCE and the 2nd century CE. The oldest complete texts we have date from the 4th century CE.

Roman Catholic versions of the Old Testament have traditionally been based on the Septuagint, while Protestant translators tend to use the Masoretic texts.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in the 1940s and 1950s and date from the centuries leading up to the catastrophic Jewish War of 66 to 73 CE. They contain fragments of almost all the books of the Old Testament. About 60% of these fragments are similar to the Masoretic texts, while some 20% resemble the Septuagint.

With the New Testament, we have an even greater variety of texts to choose from. The oldest date from the late 3rd and early 4th century CE.[15] One authoritative estimate is that there are between 200,000 and 400,000 variations in these early texts,[16] though most (but not all) are insignificant.

Do the Bible’s Contradictions Matter?

To fundamentalists and conservative Christians for whom the Bible is literally the Word of God and therefore flawless, these contradictions obviously matter a great deal. Why else would they devote so much effort to “proving” that they aren’t really contradictions at all?

But there is another very ancient Christian and Jewish tradition that embraces these contradictions, arguing that God put them there to remind us not to get hung up on the surface meaning of the text but to look behind it to find the text’s deeper, spiritual meaning.[17] People who think this way still see the Bible as the Word of God, but they have a more questioning, thoughtful faith.

Atheists and more liberal Christians argue that these contradictions show the human origins of the Bible. Liberal Christians still draw inspiration from the Bible, which some see as the story of how Jews and Christians discovered God.[18] But for atheists and liberal Christians alike, these contradictions disprove fundamentalist interpretations of the Bible. How can it be literally true if it doesn’t even agree with itself?

But, whether you draw inspiration from the Bible or simply read it as literature, these contradictions don’t diminish its depth. Isn’t an anthology that contains multiple points of view inherently richer than one limited to a single viewpoint? Those who take the Bible literally not only fail to understand its history, they also lose sight of the wealth it contains.

[1] https://friendlyatheist.patheos.com/2013/08/19/an-incredible-interactive-chart-of-biblical-contradictions/ (accessed 31 March 2024).

[2] This story is told in Friedman, Richard Elliot. Who Wrote the Bible? Jonathan Cape, London 1988, pp 50-70.

[3] Hayes, Christine, Introduction to the Bible (Kindle Edition), Yale University Press 2012, Loc 1067-1090.

[4] The first version is Genesis 1 and the second version is Genesis 2 from verse 4.

[5] In my novel The Omega Course, I show the two versions of Noah, first separately and then woven together as they are found in the Bible. You can see this without buying the book. Click on the paperback, click on Read Sample and then scroll down to Appendix One on page 365. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Omega-Course-novel-guilt-redemption/dp/B0CTD1PF1G/

[6] See Friedman op cit, pp 190-191, 196-197.

[7] Brettler, Marc Zvi: The Creation of History in Ancient Israel, Routledge, London 1995; pp. 21-22, 24-25.

[8] Neill, Stephen and Wright, Tom: The Interpretation of the New Testament 1861-1986, Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988, pp. 127-8.

[9] Sheehan, Thomas: The First Coming: How the Kingdom of God Became Christianity, Crucible, Wellingborough 1988, p. 74.

[10] Neill, Stephen and Wright, Tom: The Interpretation of the New Testament 1861-1986, Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988, pp. 28, 112-3.

[11] Sanders, EP: The Historical Figure of Jesus, Penguin Books, London 1995, pp. 66-73.

[12] Hayes, Christine, Introduction to the Bible (Kindle Edition), Yale University Press 2012, Loc 6605.

[13] Ecclesiastes 7:15.

[14] Barton, John: A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths, Penguin Random House, London 2020, pp. 300-306.

[15] Barton, John: A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths, Penguin Random House, London 2020, pp. 285-293.

[16] Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperSanFrancisco, 2005, pp. 87-89

[17] Barton, John: A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths, Penguin Random House, London 2020, pp. 339-350.

[18] A book that takes this approach is Stark, Thom, The Human Faces of God, What Scripture Reveals When It Gets God Wrong (And Why Inerrancy Tries to Hide It),WIPF & Stock, 2011.

Leave a comment